It has become increasingly apparent that researching the early motor industry also involves an exploration of the cycle industry and its customers. A few blogposts ago I did a brief analysis of the Manchester and Salford cycle industry. However, this blog looks outwards at Manchester’s suburban cycle makers, exploring the links between them and the early motor industry. The suburban areas are the surrounding towns that make up what is now Greater Manchester, such as Stockport, Altrincham and Eccles.

Manchester’s suburban trade directories show some interesting trends in cycle making in the suburbs. Firstly, as can probably be expected, in more residential areas around Manchester there were fewer cycle makers. In 1899 there were roughly 160 cycle makers (some of these agencies) within a 2 mile radius of the city centre. Outside of this radius there were only 25 cycle makers.

Significantly amongst these 25, 17 were situated in towns south of Manchester, in the richer suburbs. Affluent middle-class towns such as Altrincham had as many as 4 cycle makers, while Wilmslow, Sale and Heaton Moor had two each; whereas working-class towns such as Stockport had none. This probably shouldn’t come as a surprise. Cycling in Victorian Britain was a rich persons past-time, bicycles being outside the price range of the working-class, who would have had to spend several months worth of wages to be able to afford one. Towns such as Altrincham, Sale and Wilmslow were also situated next to the Cheshire countryside, very popular with cyclists, both then and now.

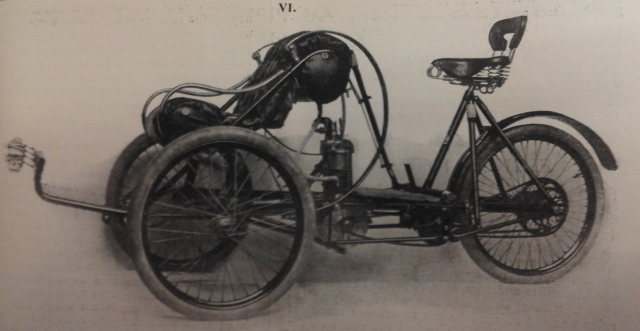

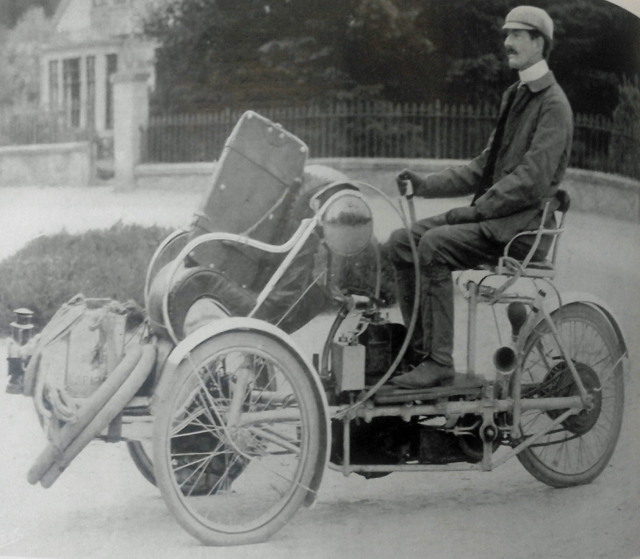

A few of these suburban cycle makers also turned to motor manufacture. Was this an attempt to cater for the changing hobbies of their local punters who were switching from cycling to motoring? James Bowen cycle maker of Heaton Moor was one. The other was Ralph Jackson, the maker of “Ralpho” Cycles in Altrincham, one of the earliest of Manchester’s cycle makers to experiment with motor vehicle production. Prehaps Jackson was looking to get ahead of this 3 local rivals. Jackson formed Century Engineering and Motor Company in 1899, producing the first finished vehicle, the Century Tandem by November 1899 where it appeared for the first time at the Stanley Cycle Show.

The tandem had some interesting features, and clearly showed Jackson’s 15 years experience in the cycle industry. Notice in the image the cycle tubing, the driver’s sprung saddle, the cycle wheels and the cycle gearing. Novel though, was the well-sprung and rather conformable looking front passenger seat, the petrol tank housed under the passengers head! Steering was done by a lever, which was presumably moved backwards and forwards to turn either left or right. Braking was especially crude on the Century Tandem; the rear mudguard was pushed by the driver’s heel, onto the tyre to bring the vehicle to a stop. The engine and carburettor were of French make and the chain transmission was made by world renowned, Manchester chain manufacturer Hans Renold, who were quick to produce specialised motor vehicle chains. Buying in specialist parts was common during this early period of experimental construction.

The Century Tandem had a significant lifetime. One was entered in the 1,000 mile trial of 1900, with only a few other British manufacturers. It completed the course and surely led to a number of orders. Some of the subsequent customers would write to The Autocar and tell of their experiences. One customer, Leopold Canning (later the 4th Baron of Garvagh), liked the Century so much that he ordered three of them, calling two the “Scarlet” and “Chocolate” Century. Canning describes a tour he took from the works in Altrincham, through Wilmslow and Alderley Edge and up the “Wizard” Hill, before touring up to the Cat and Fiddle outside Macclesfield, stopping for a drink and “free-wheeling” home.

It is likely that the number of orders after the 1,000 mile trial, reported as £12,000 worth, led Jackson and his partner Sydney Begbie (an ex-cycle works manager) to move production down to Willesden Junction, London, much nearer to the company’s newly opened show rooms in Holborne Viaduct, a road on which many motor traders had their offices. At some point during 1900-1901 Ralph Jackson fell out with his partner, he left the business and returning to his home town of Altrincham to set up the Eagle Motor and Engineering Company and made a similar tandem which he continued to sell, from Altrincham for several years. One wonders why the firm moved to London. Did they want to be nearer the large South Eastern customer base? Was being stationed near a major railway line a significant economic advantage? Had they outgrown Altrincham?

Sources for this blog include:

Slater’s Manchester and Salford Suburban Trade Directory 1899 and The Autocar held at the Central Library.

J. Wyatt, “The Eagle Motor and Engineering Co. Ltd.” In Old Motor and Vintage Commercial, Sept 1963 and A. D. George, “The Rise and Fall of the Manchester Motor Industry”, in d. Brumhead and T. Wyke, Moving Manchester, 2004.